By: Kisella Valignota, Communications Director

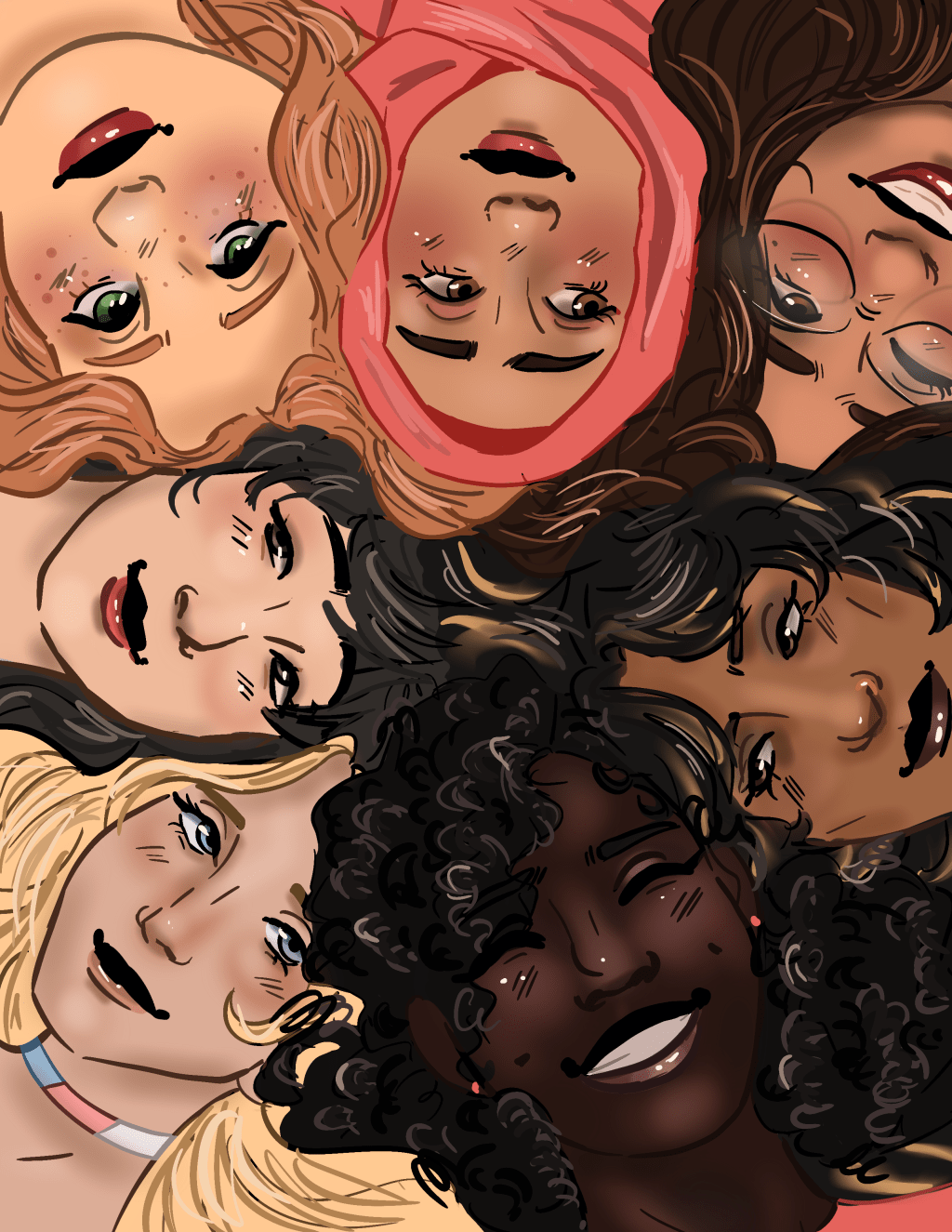

illustration By: Lynleigh (Lyn) Ufen, design executive

Last month, many took the time to honor Women’s History Month and reflect on the achievements that women before us have accomplished that shape the society women live in today. However, as feminism and the women’s rights movement continue to progress, many divisions have branched out that both directly and indirectly exclude communities based on race, class, gender identity or career.

We’ve seen this type of exclusion since one of the first organized conventions in the women’s rights movement, the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. Although there were previous historical events that addressed the fight for women’s rights, many regard the convention as a pivotal moment for women and the first wave of feminism. During this meeting, they discussed and voted on a document that listed women’s rights grievances, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, titled the Declaration of Sentiments by activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In The National Women’s History Museum’s article, “Feminism: The First Wave,” the organization described how the convention “advocated for women’s education, right to property, and organizational leadership. One of the most controversial topics on the program was women’s suffrage. Although not everyone agreed, many of these women’s rights activists believed that their goals would be hard to accomplish without the right to vote.”

As the Seneca Falls Convention highlighted the significance of voting, the event served as a catalyst for the women’s suffrage movement. Unfortunately, as many women suffrage activists consisted of middle and upper-class white women, this left the intersectionality of struggles for women of color or of lower class, forcing them to work twice as hard to be seen, respected, and ultimately given their rights.

“…For other groups of women, the right to vote was not only tied to their gender, but it was also tied to their race and social class. As the movement progressed, the concerns of women of color were often overlooked by first wave feminists,” the group of writers from the National Women’s History Museum said. “Despite often being uninvited or excluded from fully participating in white organizations, women of color spoke out about facing not only sexism, but also racism, and classism.”

This overlap in struggle based on identity is a primary reason for the exclusions that exist within modern feminism. Professor of English Jeanne McDonald has been a teacher at Waubonsee Community College for over 20 years, instructing both introductory English classes and different branches of literature. Having taught the Women’s Literature course and harboring a personal love for interdisciplinary work, McDonald has studied many historical women figures and how the fight for their rights developed over time.

“In terms of just studying how women’s rights developed, [I see] the abolitionist movement as a companion movement that happened at the same time,” McDonald said. “Abolitionists were one of the first ones who allowed platforms for women to speak and to write articles in newspapers, and to actually do actions that would advocate for women [such as] use their right of petition, and influence their male counterparts so that they could vote in ways that they could agree on.”

During the early 1860s, leaders of both the women’s suffrage and abolition movements worked together in support of universal suffrage, regardless of race or gender. This alliance unfortunately fell apart after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1868, which came in response to slavery and addressed the rights of formerly enslaved people.

The article “Fighting for Suffrage: Comrades in Conflict” by National Park Service intern Megan Bailey, states, “because the amendment did not grant the universal right to vote, abolitionists and some suffragists withdrew from the universal suffrage campaign to focus on the enfranchisement (obtaining the right to vote) of Black men. Some of those involved in the suffrage movement also divided over whether to support the Fifteenth Amendment, which would protect the rights of Black men but did not include women.”

While leaders from the civil rights movement clashed with those from the women’s rights group, it led to a divide that forced fellow activists to decide where to prioritize their work. However, the levels of the enfranchisement issues in America were not simple enough to water down as two choices. This conflict left many communities, such as Black women, who were notoriously excluded by both movements, as seen during their lack of presence at the Seneca Falls Convention, to campaign separately from the major forces.

“[Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony] thought that trying to attain the vote for both African Americans and women at the same time would be impossible. They could not envision a way that everyone’s voice could be heard. Meanwhile, many Black women continued to campaign for universal suffrage, knowing that discrimination based on race and sex were equally unacceptable,” Bailey said.

These marginalizations of Black women demonstrate how the tensions of the simultaneous movements left room for racism in spaces that advocated for women. Additionally, this discrimination wasn’t slight either, considering the significance of major suffragettes speaking on it. Anthony famously says, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the negro and not the woman.”

Although this quote comes in reaction to the discourse over the 15th Amendment’s exclusion of women, it specifically highlights the lack of interdisciplinary work within the women’s rights movement and how history has come to overlook its racism. Many credit Anthony as a leader during this social reform and a fighter for equality. However, she falls short as a champion of women in her discrimination towards Black Americans and women of color.

Because of her accomplishments in women’s suffrage, these discriminative parts of her work and their impacts often go unnoticed when we look back on history. Disregarding this and continuing to learn select parts of Anthony and other opposing suffragettes’ pasts come from a place of privilege. Unfortunately, this trend has continued within the feminist movement as it has grown in modern times.

There’s no denying that the feminist movement has made large strides since the 19th Amendment of the Constitution in 1920 which guaranteed that women had the right to vote. However, there is still a significant amount of progress that needs to be made that is inclusionary and both addresses and meets the needs of all women, regardless of race.

A common form of feminism that is criticized for its exclusionary actions is called white feminism. This term refers to feminism that typically neglects the idea that oppression works in intersectional ways through race, class or ability, and instead has a tendency to prioritize the needs of middle to upper-class white women. In her interview with news outlet Mashable, Author of White Feminism Koa Beck discusses the idea’s harm in white feminism.

“White feminism acts to homogenise feminism: to assert mainstream dominant feminism as The Feminism, which is not true; this is an act of white supremacy,” Beck said. This dynamic often means that where the needs of women of colour, transgender women, disabled women, or Muslim women conflict with that of white supremacy, their needs will be dismissed or subjugated. The one Black woman in the ‘feminist’ meeting has her ideas dismissed because they are ‘too niche’ (i.e. only for non-white women).”

Additionally, this negligence not only fosters prejudice in spaces but can easily exist in places of naivety or ignorance. By failing to address the faults in social systems that discriminate against women, many end up inadvertently advocating for white feminism and only who it serves. We can see multiple examples of this in common feminist demonstrations: advocating for reproductive rights but failing to acknowledge menstrual hygiene accessibility for low-income women, overlooking the presence of racial police brutality and only focusing on how it occurs in sexism, addressing the gender pay gap but not as it pertains to women of color which perpetuates racial wealth inequality or assuming Western norms are feminist norms to non-Western women that need “saving” rather than uplifting their voices.

These white feminism practices have become very common, especially in large movements or through media outlets. Because of this, individuals who may mean well end up indulging in it. Regardless of the intent, indirectly participating in white feminism contributes to the oppression of women of color and other marginalized communities. McDonald finds that, with these complex levels of feminism, it’s important to hold true to the universal equality that the movement advocates for.

“What was not helpful [to women’s rights] was that white women came first with the vote, then Black women, then Chinese women, and then Native Americans who claimed their birthright citizenship rights. And so, those many competing voices, along with the immigrants who came, had varying degrees of family life, family culture and how they saw themselves in terms of [their] relationships to men…” McDonald said. “What I like best about the feminist movement is that they recognize that, first of all, it’s a human rights issue. When they are working in other countries and so forth to create rights and space for women, they see it as a human right and a way to validate themselves in a sense and other women.”

McDonald believes that, although there was a historical divide, the universality of human rights exists in spaces that serve women regardless of dissimilarity. However, the exclusions and privileges of certain women over others continued well past the suffragettes.

As the women’s rights movement continued to progress into the 1960s, along came second-wave feminism and the creation of the Radical Feminist Movement. This sub-branch focused on systematic change, and specifically highlighted the patriarchy as the root of women’s oppression; displays of this existed in violence against women, sexual objectification and traditional gender roles. The motion especially targeted dismantling the latter due to infringements on the freedoms of women, but unfortunately, this led some radical feminists to a fixated view on the gender binary and the overall exclusion of transgender rights in spaces that advocated for women’s rights; this movement is now known as gender critical feminism, or trans-exclusionary radical feminism (TERF).

“The traditional feminists don’t wanna leave space for transgender feminism, mostly because of the gender issue and whether or not that can be bridged. However, in terms of transgender feminism, that kind of subverts a lot of thinking about what constitutes being a woman, what constitutes femininity, body image and body morphisms,” McDonald said.

Although society continues to progress to define these different constitutions of womanhood, people struggle to find a universal establishment. Sophomore Abigail Kleimola has seen how fragmented the feminist movement has become, especially in regards to how gender critical groups treat and exclude trans women.

“TERFs pride themselves on ‘protecting women’ but often their hatred is turned on the very women they supposedly want to protect – from a group of people who only want to be allowed to exist. Even in self-proclaimed inclusive groups, there is often a limit to that acceptance. Certain safe spaces for women, as of late, have rebranded to “female only” and have begun excluding the exceedingly vulnerable class of trans women,” Kleimola said.

The divergence of feminism goes on to exclude specific gender identity, believing that it is protecting the rights of biological women. As the topic of transgender rights becomes more prevalent in today’s political discussions, we can see how these movements have influence in current governments.

On Wednesday April 16, 2025, Breaking News Writer for CNN Sana Noor Haq reported in her article, UK Supreme Court says legal definition of ‘woman’ excludes trans women, in landmark ruling, on the landmark decision by Britain’s highest court who “ruled unanimously that the definition of a woman in equality legislation refers to “a biological woman and biological sex,”” and was discussed due to the controversy in “whether trans women with a gender recognition certificate (GRC) – which offers legal recognition of someone’s female sex – are protected from discrimination as a woman under the nation’s Equality Act 2010.”

The case stems from a dispute between the campaign group For Women Scotland (FWS) and the Scottish government, arguing whether the legislative rights should only protect women assigned at birth or not; the latter defending trans women with a GRC as legal women. FWS is a gender-critical feminist organization that is anti-trans, opposing individuals from changing the sex assigned to them at birth in legal documents.

Many citizens of the UK are concerned about what this means for the LGBTQ+ community, as the ruling works to impact changing rooms, bathrooms, hostels, hospitals, sports clubs and their accommodations for trans people. Additionally, people stress how certain policy changes will now be in effect and can have harmful consequences for both trans and cis women.

British Transport Police (BTP) have amended their strip-searching policy to abide by the new ruling, declaring that male officers would now carry out searches on trans women and vice versa. However, this policy now ignores the validity of GRC’s and primarily goes off of what the BTP perceives the detainee’s assigned sex is, especially if they don’t have documented proof with them. This has led to many women who are intersex or cis with masculine features expressing their worry on social media platforms about the exploitation of power, and that their appearance may subject them to a wrongful strip and search by a male officer.

“We’re yet to see how all of this will play out in practice, but it seems clear that this won’t just hurt the trans community. The reasoning adopted, and the relentless desire to police ‘what is a woman’ can only hurt our wider communities,” Legal Researcher Jess O’Thomson said for the LGBTQ+ news outlet QueerAF, in their article “UK Supreme Court Rules That Trans Women Aren’t Women under the Equality Act 2010.”

Although these feminist-driven organizations and policies are meant to protect women, they not only result in excluding trans people but can hurt any and all women. We see how exclusionary feminism can go on to have an impact in our governments, but furthermore, these movements have influence over the everyday conversations and perceptions society has on women.

The radical feminist movement specifically highlights the injustices women face due to the patriarchy and men overall; as this includes sexual objectification and violence, people have gone on to describe women in the sex work community as a threat to women’s rights and feminism. This belief evolved into a sub-branch similar to TERFs, Sex Work(er) Exclusionary Radical Feminism (SWERF). McDonald explains how this modern take has been present in society long before radical feminists and is intertwined with traditional and religious views that shame sexuality and sexual expression.

“There’s an old age tale in literature and culture that women were either seen as saints or whores. And so, sex work highlights a lot of the divisions – especially religious and moral ones – that have been placed on women’s behavior. And when you’re looking at sex work and that normalization, what you’re seeing is, for a lot of people who come from really defined moral systems, that that violates their sense of propriety and their sense of – for lack of better word – righteous behavior,” McDonald said.

Many religious groups have fostered a large influence over how today’s society will view sex workers, and this consequently denies them from the feminist community. The conservative angle that SWERFs come from upholds the internalized misogyny that exists in today’s world, associating the value of a woman with her sexuality. However, the universality of feminism works to look past religious barriers, and thus should not be constrained to what a woman’s professional pursuits are.

“So when you talk about normalizing sex workers, the main concern there is that we know that human behavior will find some way to support themselves and do the work they do without necessarily thinking about the moral world. So what comes next? Well, human rights,” McDonald said.

People who advocate for sex workers say that their embrace of sexuality is empowering, specifically as a response to the sexual oppression that women have faced for centuries. However, beyond this argument lies the actual safeguard necessary for women in the field. Recognizing women’s history of sexual violence, it is necessary for women to be protected when working in a career that could jeopardize their safety, and it is important not to blame the workers for the system’s doing. Even though the modern argument for SWERFs comes from a place of protecting women from exploitation and violence, it backfires into a lack of support for the safety of the people in the sex work community.

“Everybody deserves to be safe. Everybody deserves to be healthy. Everybody deserves to have as much freedom about the happiness and the choices that they make. When you start looking at sex workers from a human rights standpoint rather than a moral or ethical standpoint, then you see space for women’s rights and women’s protections,” McDonald said. “Those protections are…health issues and getting regular examinations, to be able to define their own work rather than being exploited by sex traffickers of any kind and whether or not they’re getting paid fairly for the work and the investment that they do.”

Many people associate sex work with the criminality of prostitution, which is illegal in 49 states in the United States, but working in the industry also includes indirect services such as erotic dancing or adult films. Criminalizing sex work between two consenting adults perpetuates stigmas that marginalizes the workers and highlights systematic and policy issues that harm women, putting their health and safety at risk. Failing to reform the industry into a safe space where workers can earn an income not only hurts those involved, but also encourages people to seek harmful alternatives and encourages false narratives about sex work. Recognizing that sex workers are also humans is necessary for feminist pursuits, and choosing not to listen to their needs as people is not only harmful to their community but to all women who are protected by human rights.

“Feminism has very noticeably fractured into different, exclusive groups. These fringe groups have existed on the outskirts of feminism for a long time, and my opinion is that these people are not true feminists at all. To exclude any women from your activism not only negates any messages of equality and inclusion, but also damages the integrity and strength of the group,” said Kleimola. “At its core feminism has always been, to some degree, about the intersectionality between different issues. Focusing feminism on the experiences of only a specific group of women excludes those who have done important work throughout feminist history and women who should be supported as part of the community.”

The idea of feminism recognizes the social, political and cultural equality and safety of all women, and selectively deciding who is entitled to those protections and rights is not only dangerous, but fails to follow the true universality of feminism. We cannot continue to overlook how the empathy and humanity that exists within the movement is inherent.

“Even though we’re struggling in the present day to figure out what is a man, what is a woman, what we’re really struggling to promote is what is human. Wherever that humanity happens – whether it’s in a male body, female body, a mixed body, a trans body, and whatever race, ethnicity, religion or creed – that’s not what matters. We’re losing sight of what’s human and to condemn somebody because they don’t have the right race or the right creed or ideology or whatever – we had to pull back from that. And we have to really, really, celebrate human-ness,” McDonald said. “We’ve already made great strides and opportunities for women, but what I want [students] to understand is that no matter where their own culture is or their own connections are, they have agency. They can work and they can take advantage of opportunities that come their way because they are valuable humans.”

Leave a comment